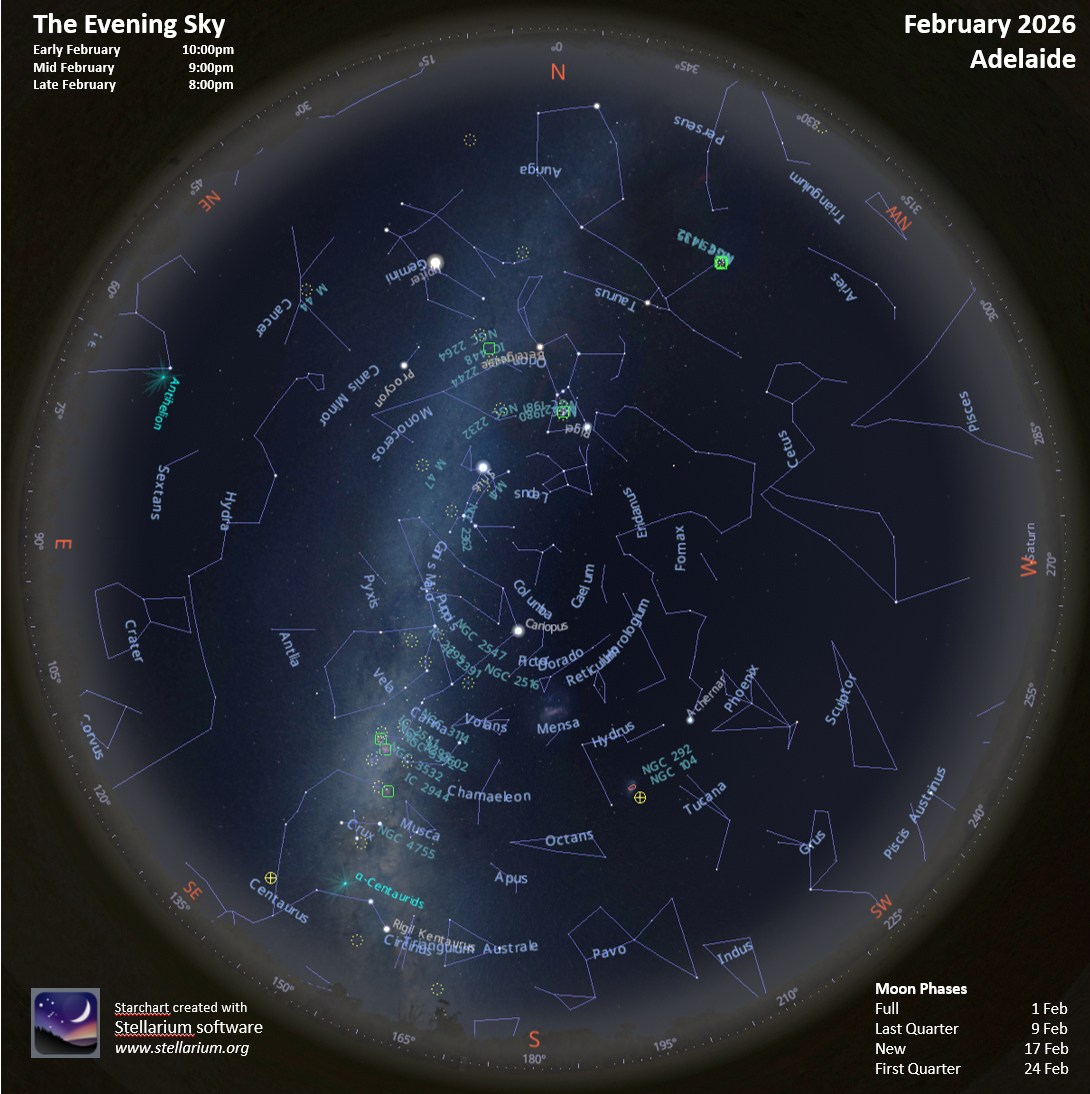

A guide to what's up in the sky for Southern Australia

Starwatch for February 2026 - Mon 2nd Feb 2026

Published 2nd Feb 2026

During these warm February evenings, the summer Milky Way is visible directly overhead, running north-south across the sky. The evening sky is resplendent with many brilliant stars. From Capella in the north to the Pointers in the south, the sky is a sheer delight to explore.

NGC 2439—Open Star Cluster - Sun 1st Feb 2026

Published 1st Feb 2026

NGC 2439—Open Star Cluster - Distance: 12,500 light years

Starwatch for January 2026 - Tue 30th Dec 2025

Published 30th Dec 2025

We can think of our location in the universe along the lines of an address. The street would be planet Earth, the local government area would be the solar system, and the country would be the Milky Way Galaxy.

M1 - the Crab Nebula - Mon 29th Dec 2025

Published 29th Dec 2025

Distance: 6,500 light years

Starwatch for December 2025 - Tue 25th Nov 2025

Published 25th Nov 2025

All the stars we see in the night sky belong to our Milky Way galaxy. However, there are some objects outside of the Milky Way galaxy that can be seen quite clearly with no or little optical power.

Starwatch for November 2025 - Wed 29th Oct 2025

Published 29th Oct 2025

A 101 years ago, on November 23, 1924, the universe got larger.

Starwatch for October 2025 - Thu 2nd Oct 2025

Published 2nd Oct 2025

Astronomical distances can be mind boggling. Our closest neighbour, the Moon, is 380,000 kms away — equal to about 10 trips around Earth’s equator.

Starwatch for September 2025 - Wed 3rd Sep 2025

Published 3rd Sep 2025

A few lingering stars of winter are still in view during the evening. Antares, Altair, Vega have lit up the cold winter nights for us. But there is really only one bright star that puts in its best showing during these early spring nights:

NGC 7293 – The Helix Nebula - Tue 2nd Sep 2025

Published 2nd Sep 2025

Image © Patrick Cosgrove. The Helix Nebula, also known as NGC 7293, is a planetary nebula (PN) located in the constellation Aquarius.

Starwatch for August 2025 - Sun 3rd Aug 2025

Published 3rd Aug 2025

Imagine yourself sitting on a rock on the dark side of Moon, gazing up at the Milky Way. There's no stray lights, no atmosphere to dull your view of the night sky. The stars are so brilliant, so big, you could reach out and touch them.

NGC 4755 - Fri 1st Aug 2025

Published 1st Aug 2025

The Jewel Box Star Cluster. Image © Sergio Equivar, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Starwatch for July 2025 - Thu 3rd Jul 2025

Published 3rd Jul 2025

Look up overhead on any of these frosty winter’s nights, and if you have a dark area away from direct lighting, you’ll see the Milky Way shining brightly.

Galaxy NGC 6744 in Pavo - Wed 2nd Jul 2025

Published 2nd Jul 2025

This is NGC 6744, a spiral galaxy bearing similarities to our home galaxy, the Milky Way.

Starwatch for June 2025 - Mon 2nd Jun 2025

Published 2nd Jun 2025

The winter Milky Way shines across the sky from east to west in a blaze of starlight.

Eta Carinae Nebula (NGC 3372) - Sun 1st Jun 2025

Published 1st Jun 2025

Eta Carinae Nebula (NGC 3372) Distance: 7500 Light Years

Starwatch for May 2025 - Wed 30th Apr 2025

Published 30th Apr 2025

We have recently seen the destructive power of extreme weather events, such as cyclones and the flooding in southwest Queensland. It left in its wake flooded businesses, broken roads, power outages, and other problems. The repair bill will run into billions of dollars.

NGC 5139 - Omega Centauri - Tue 29th Apr 2025

Published 29th Apr 2025

Globular Cluster in Centaurus

Starwatch for April 2025 - Wed 2nd Apr 2025

Published 2nd Apr 2025

The crisp autumn evenings of April offer an ideal opportunity to explore the majesty of the southern sky. Go find yourself a nice dark spot in the back-garden, and let your eyes become accustomed to the darkness. Notice how many more stars you can see, even after a few minutes, as the pupils of your eyes expand to let as much light in as possible.

IC434 -The Horsehead Nebula - Tue 1st Apr 2025

Published 1st Apr 2025

Distance: 1500 Light Years |Constellation - Orion

Starwatch - March 2025 - Mon 3rd Mar 2025

Published 3rd Mar 2025

There's nothing more magical than to lie down on your back lawn on a warm summer evening and gaze up at the brilliant night sky.

Eta Carinae Nebula (NGC 3372) - Sat 1st Mar 2025

Published 1st Mar 2025

Distance: 7500 Light Years

Starwatch - February 2025 - Wed 5th Feb 2025

Published 5th Feb 2025

Two bright beacons hold centre stage in our night sky during February. In the beautiful pastel hues of an Australian summer sunset.

M104 - The Sombrero Galaxy - Tue 4th Feb 2025

Published 4th Feb 2025

Distance: 31 Million Light Years

Starwatch - January 2025 - Wed 1st Jan 2025

Published 1st Jan 2025

There's nothing more magical than to lie down on your back lawn on a warm summer evening and gaze up at the brilliant night sky.

The Pleiades star cluster - Tue 31st Dec 2024

Published 31st Dec 2024

The Pleiades star cluster (The Seven Sisters) Distance: 435 Light Years

Starwatch - December 2024 - Sun 1st Dec 2024

Published 1st Dec 2024

The stars that shine at night do so from immense distances.

Starwatch - November 2024 - Mon 4th Nov 2024

Published 4th Nov 2024

We recently saw the destructive power of hurricanes Milton and Helene, as they cut a path of destruction through various states in the US. They left in their wake flooded businesses, broken roads, power outages, and other problems. The repair bill will run into billions of dollars.

Large Magellanic Cloud - Fri 1st Nov 2024

Published 1st Nov 2024

Distance: 163,000 light years Right Ascension 05 : 23.6 Declination -69 : 45

Starwatch - October 2024 - Mon 30th Sep 2024

Published 30th Sep 2024

After a spectacular encounter with Pluto back in July 2015, the New Horizons spacecraft was redirected to visit a more distant object, known as 2014 MU69.

OCTOBER’S DEEP SKY HIGHLIGHT - Sun 29th Sep 2024

Published 29th Sep 2024

M31—The Andromeda Galaxy Distance: 2.5 million Light Years

Starwatch - September 2024 - Sat 31st Aug 2024

Published 31st Aug 2024

Spring is just around the corner, and with it, comes the promise of warmer evenings and clearer skies. And hopefully the opportunity to spend more time looking up!

NGC 253 – Galaxy in Sculptor - Fri 30th Aug 2024

Published 30th Aug 2024

NGC 253 is the brightest member of the Sculptor Group of galaxies.

Starwatch - August 2024 - Tue 30th Jul 2024

Published 30th Jul 2024

f you're brave enough to venture outside these cold winter nights, you'll be greeted by the heart of our Milky Way galaxy directly overhead. Find yourself a dark space in your backyard on a clear moonless night, and look straight up.

The Swan Nebula - Mon 29th Jul 2024

Published 29th Jul 2024

M17 – The Swan Nebula in Sagittarius

Starwatch July 2024 - Mon 8th Jul 2024

Published 8th Jul 2024

Look up overhead on any of these frosty winter’s nights, and as long as you have a dark area away from direct lighting, you’ll see the band of the Milky Way shining brightly.

Merging Galaxies - Sun 7th Jul 2024

Published 7th Jul 2024

NGC 4038-4039 Merging Galaxies - The Antennae. Distance: 45 million Light Years.

Starwatch June 2024 - Sun 2nd Jun 2024

Published 2nd Jun 2024

About half-way up the northern evening sky, a bright star shines.

The Trifid Nebula - Sat 1st Jun 2024

Published 1st Jun 2024

M20 – The Trifid Nebula in Sagittarius

Starwatch May 2024 - Thu 2nd May 2024

Published 2nd May 2024

A myriad of bright stars adorn the late autumn evening sky.

Galaxy NGC 5128 - Wed 1st May 2024

Published 1st May 2024

Galaxy NGC 5128—Centaurus A

Comet Pons-Brooks - Wed 10th Apr 2024

Published 10th Apr 2024

Looking west on the evening of April 27., 30 minutes after sunset. Locate the orange star Aldebaran, then scan to the left until you come to a fuzzy spot in the sky. Train your binoculars on it, the comet will be 239 million kilometres away. Graphic generated with Stellarium planetarium software.

M104 - The Sombrero Galaxy - Tue 9th Apr 2024

Published 9th Apr 2024

M104 - The Sombrero Galaxy. Distance: 31 Million Light Years

Starwatch - April 2024 - Mon 8th Apr 2024

Published 9th Apr 2024

Some of the brightest stars in the whole sky can be seen during these crisp autumn evenings.

Starwatch - March 2024 - Wed 6th Mar 2024

Published 6th Mar 2024

What a wonderful time of the year this is to be observing the night sky. The weather is warm, the nights clear, and the Milky Way shines directly overhead!

Object of the Month - Mon 4th Mar 2024

Published 4th Mar 2024

Eta Carinae Nebula (NGC 3372)

Distance: 7500 Light Years

Right Ascension: 10 : 43.8 | Declination: -59 : 52

During these warm February evenings, the summer Milky Way is visible directly overhead, running north-south across the sky. The evening sky is resplendent with many brilliant stars. From Capella in the north to the Pointers in the south, the sky is a sheer delight to explore.

Just to scan this area with binoculars is like taking a walk along a road of glittering stardust.

The two brightest stars in the night sky are easily seen at this time of the year. Look straight up when it gets properly dark, and you’ll be greeted by Sirius, the brighter of the two, high in the northern sky. Now, turn around and look high in the south. You’ll be greeted by Canopus, the second brightest star.

Canopus is the brightest star of Carina. The constellation represents the bulk of the Argo, the ship that carried Jason and the Argonauts on their adventures.

Although the star Canopus looks only about half as bright as Sirius, that’s only because of its greater distance. It’s more than 300 light-years away, compared to nine light-years for Sirius. If you lined them up at the same distance, Canopus would shine more than 500 times brighter.

Studies conducted some 30 years ago with an orbiting space telescope helped astronomers to establish its distance accurately, and to compile a better profile for the star. It’s about 8 to 10 times as massive as the Sun, and more than 70 times the Sun’s diameter. The great size tells us that Canopus is nearing the end of its life, so it’s puffed outward. Over the next million years or so it may get even bigger and brighter. And while the star is already a good beacon for interplanetary travel, the extra brilliance would enhance that role.

There’s evidence that Canopus helped people get their bearings for centuries. Canopus helped Polynesian sailors navigate from island to island. It also helped European sailors when they began to journey through the southern hemisphere.

And it’s still a popular beacon today; not for people, but for spacecraft. When NASA began planning missions to the Moon and planets in the 1960s, it needed a star to serve as a handy navigational beacon. Locking on to the star and the Sun would keep a craft on target. Canopus was the obvious choice. Not only is it bright, it’s also well away from the ecliptic; the Sun’s path across the sky. That means there’s always a good separation between Sun and star, so they’re both always in view. And there are no other bright stars or planets around it to confuse the tracking system. Canopus made its debut with the Surveyor missions to the Moon and Mariner missions to the planets. And it still helps guide spacecraft today, on journeys across the solar system and beyond.

Head to the north from Sirius, and you’ll be greeted by a bright blue-white star. Rigel is one of the more impressive stars in our part of the galaxy: It’s the seventh-brightest star in the night sky, it’s many times the size and mass of the Sun, and it’s fated to explode as a supernova.

But a closer look shows that Rigel is even more impressive than it seems. It appears to be a system of at least four stars. The one that’s visible to the eye alone, plus three others that are grouped fairly close together.

The companions include a binary – two stars locked in a tight orbit around each other – plus a third star that’s farther away. All three companions are three to four times the mass of the Sun. That puts them in the top one percent of all stars in the galaxy.

The stars in the binary orbit each other once every 10 days. At the system’s distance of more than 850 light-years, not even the biggest telescopes can see them as individual stars. Instead, astronomers use special instruments to tell them apart. The third star is far enough from the others that it’s easy to see on its own.

This triplet of stars is about a quarter of a light-year from the bright star that’s visible to our eyes alone. At that separation, it would take at least 24,000 years for the bright star and the triplets to orbit each other.

The bright stars in the northern sky, Sirius, Rigel, Betelguese, Procyon, Castor or Pollux cannot compete with the brilliance of the colossus of the solar system, the planet Jupiter, currently ruling over that part of the sky. It rises well before sunset amongst the stars of Gemini, the twins. It’s reflecting sunlight from a whopping distance of 645 million kilometres. Only the Moon and the planet Venus outshine it.

Jupiter is the fifth planet out from the Sun, about five times farther from the Sun than Earth is. At that distance, it takes almost 12 years for the planet to complete a single orbit around the Sun.

Jupiter is like a mini solar system. The Sun’s largest planet has a family of almost a hundred known moons. Most of them are little more than cosmic driftwood - rock and ice no more than a few kilometres wide. But a few rank among the most interesting worlds in the solar system.

The four largest moons are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. First sighted by Galileo Galilei at the end of December 1609, they account for more than 99.9 percent of the combined mass of all of Jupiter’s moons. They probably formed along with Jupiter itself, from dust and gas that encircled the newborn planet.

Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system. It’s covered by hundreds of volcanoes, lakes of molten lava, and other features. The other three big moons appear to have oceans of liquid water buried below their icy crusts. And Europa’s ocean is considered one of the most likely homes for life in the solar system.

Some of Jupiter’s little moons could have formed at the same time as the big guys, then perhaps moved into different orbits. But most of them appear to be the remains of asteroids that Jupiter captured when they wandered close. The asteroids were blasted apart in big collisions, leaving small chunks of ice and rock in orbit around the planet. It’s always fascinating the watch the dance of the four big moons around Jupiter. You can see them change position within a very short time, and occasionally you can watch the shadow of one of the moons as it transits in front of the planet.

Saturn is now lost in the glare of the setting sun. It returns to our evening skies in September, offering a better view of the rings than we’ve seen in the past year.

We calculate distances across the solar system, and with authority proclaim that Jupiter is currently 645 million kilometres away. But do we appreciate that distance? To try and put it in some perspective, imagine that the Sun is represented by a soccer ball in the middle of an oval. Put the ball down and walk ten paces in a straight line. Stick a pin in the ground. The head of the pin stands for the planet Mercury. Take another 9 paces beyond Mercury and put down a peppercorn to represent Venus. Seven paces on, drop another peppercorn for Earth. Twenty five millimetres from Earth, another pinhead represents the Moon. Fourteen more paces to little Mars, then 95 paces to giant Jupiter, a ping-pong ball. Saturn is a marble, a further 112 paces. You’ve now reached the goal posts.

But, how far would you have to walk to reach the nearest star, Proxima Centauri? Pick up another soccer ball to represent it and set off for a walk of about 7000 kilometres to Hong Kong! Enjoy your walk!

The Moon is Full on February 2, at Last Quarter on the 9th, New on the 17th and at First Quarter on February 24.

Happy observing!