A guide to what's up in the sky for Southern Australia

Starwatch for March 2026 - Fri 27th Feb 2026

Published 27th Feb 2026

It seems just like yesterday that we greeted the return of the summer stars to the evening sky, and here we are in March, getting ready to wave goodbye!!

M44—The Beehive Cluster - Wed 25th Feb 2026

Published 25th Feb 2026

The Beehive Cluster is an open cluster in the constellation Cancer.

Starwatch for February 2026 - Mon 2nd Feb 2026

Published 2nd Feb 2026

During these warm February evenings, the summer Milky Way is visible directly overhead, running north-south across the sky. The evening sky is resplendent with many brilliant stars. From Capella in the north to the Pointers in the south, the sky is a sheer delight to explore.

NGC 2439—Open Star Cluster - Sun 1st Feb 2026

Published 1st Feb 2026

NGC 2439—Open Star Cluster - Distance: 12,500 light years

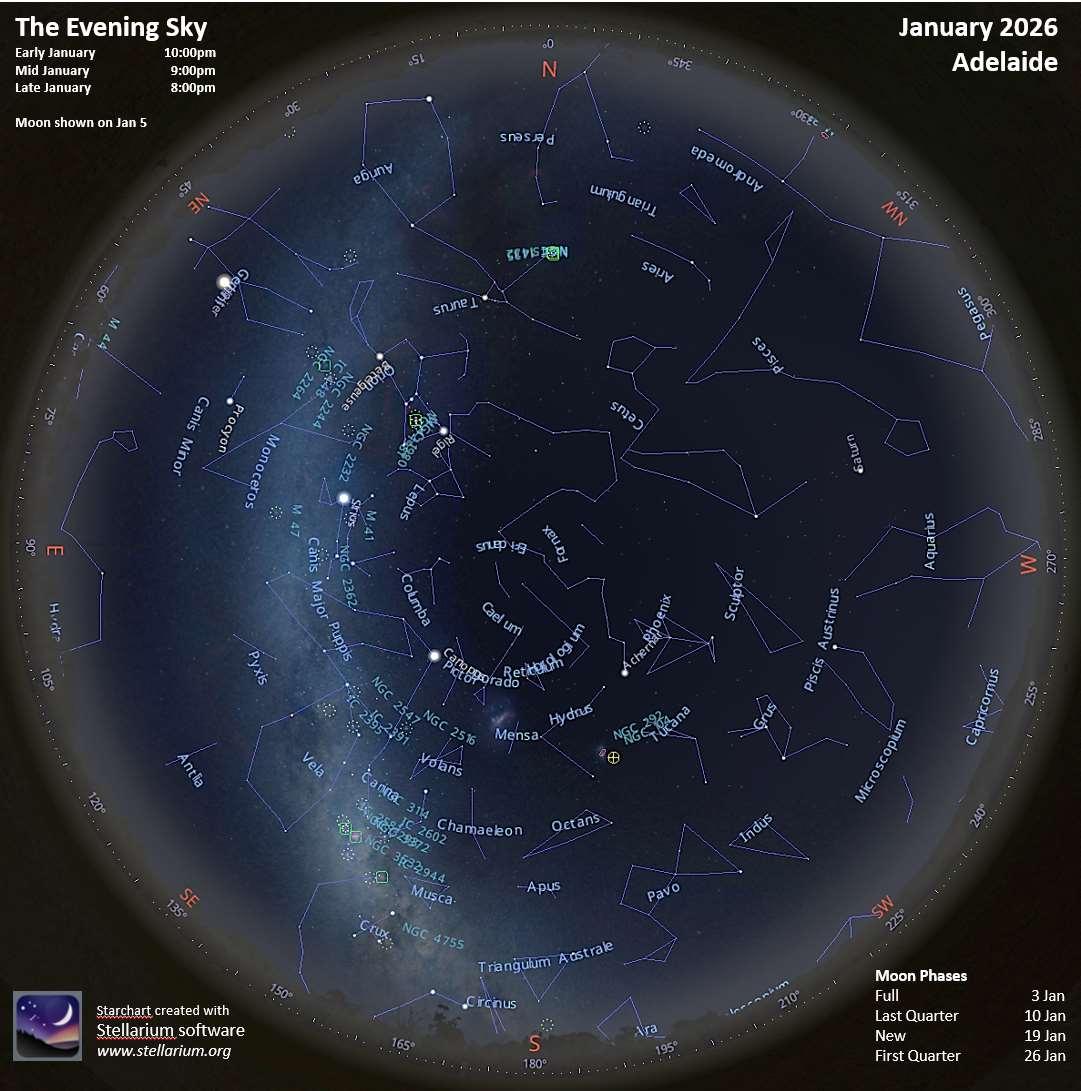

Starwatch for January 2026 - Tue 30th Dec 2025

Published 30th Dec 2025

We can think of our location in the universe along the lines of an address. The street would be planet Earth, the local government area would be the solar system, and the country would be the Milky Way Galaxy.

M1 - the Crab Nebula - Mon 29th Dec 2025

Published 29th Dec 2025

Distance: 6,500 light years

Starwatch for December 2025 - Tue 25th Nov 2025

Published 25th Nov 2025

All the stars we see in the night sky belong to our Milky Way galaxy. However, there are some objects outside of the Milky Way galaxy that can be seen quite clearly with no or little optical power.

Starwatch for November 2025 - Wed 29th Oct 2025

Published 29th Oct 2025

A 101 years ago, on November 23, 1924, the universe got larger.

Starwatch for October 2025 - Thu 2nd Oct 2025

Published 2nd Oct 2025

Astronomical distances can be mind boggling. Our closest neighbour, the Moon, is 380,000 kms away — equal to about 10 trips around Earth’s equator.

Starwatch for September 2025 - Wed 3rd Sep 2025

Published 3rd Sep 2025

A few lingering stars of winter are still in view during the evening. Antares, Altair, Vega have lit up the cold winter nights for us. But there is really only one bright star that puts in its best showing during these early spring nights:

NGC 7293 – The Helix Nebula - Tue 2nd Sep 2025

Published 2nd Sep 2025

Image © Patrick Cosgrove. The Helix Nebula, also known as NGC 7293, is a planetary nebula (PN) located in the constellation Aquarius.

Starwatch for August 2025 - Sun 3rd Aug 2025

Published 3rd Aug 2025

Imagine yourself sitting on a rock on the dark side of Moon, gazing up at the Milky Way. There's no stray lights, no atmosphere to dull your view of the night sky. The stars are so brilliant, so big, you could reach out and touch them.

NGC 4755 - Fri 1st Aug 2025

Published 1st Aug 2025

The Jewel Box Star Cluster. Image © Sergio Equivar, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Starwatch for July 2025 - Thu 3rd Jul 2025

Published 3rd Jul 2025

Look up overhead on any of these frosty winter’s nights, and if you have a dark area away from direct lighting, you’ll see the Milky Way shining brightly.

Galaxy NGC 6744 in Pavo - Wed 2nd Jul 2025

Published 2nd Jul 2025

This is NGC 6744, a spiral galaxy bearing similarities to our home galaxy, the Milky Way.

Starwatch for June 2025 - Mon 2nd Jun 2025

Published 2nd Jun 2025

The winter Milky Way shines across the sky from east to west in a blaze of starlight.

Eta Carinae Nebula (NGC 3372) - Sun 1st Jun 2025

Published 1st Jun 2025

Eta Carinae Nebula (NGC 3372) Distance: 7500 Light Years

Starwatch for May 2025 - Wed 30th Apr 2025

Published 30th Apr 2025

We have recently seen the destructive power of extreme weather events, such as cyclones and the flooding in southwest Queensland. It left in its wake flooded businesses, broken roads, power outages, and other problems. The repair bill will run into billions of dollars.

NGC 5139 - Omega Centauri - Tue 29th Apr 2025

Published 29th Apr 2025

Globular Cluster in Centaurus

Starwatch for April 2025 - Wed 2nd Apr 2025

Published 2nd Apr 2025

The crisp autumn evenings of April offer an ideal opportunity to explore the majesty of the southern sky. Go find yourself a nice dark spot in the back-garden, and let your eyes become accustomed to the darkness. Notice how many more stars you can see, even after a few minutes, as the pupils of your eyes expand to let as much light in as possible.

IC434 -The Horsehead Nebula - Tue 1st Apr 2025

Published 1st Apr 2025

Distance: 1500 Light Years |Constellation - Orion

Starwatch - March 2025 - Mon 3rd Mar 2025

Published 3rd Mar 2025

There's nothing more magical than to lie down on your back lawn on a warm summer evening and gaze up at the brilliant night sky.

Eta Carinae Nebula (NGC 3372) - Sat 1st Mar 2025

Published 1st Mar 2025

Distance: 7500 Light Years

Starwatch - February 2025 - Wed 5th Feb 2025

Published 5th Feb 2025

Two bright beacons hold centre stage in our night sky during February. In the beautiful pastel hues of an Australian summer sunset.

M104 - The Sombrero Galaxy - Tue 4th Feb 2025

Published 4th Feb 2025

Distance: 31 Million Light Years

Starwatch - January 2025 - Wed 1st Jan 2025

Published 1st Jan 2025

There's nothing more magical than to lie down on your back lawn on a warm summer evening and gaze up at the brilliant night sky.

The Pleiades star cluster - Tue 31st Dec 2024

Published 31st Dec 2024

The Pleiades star cluster (The Seven Sisters) Distance: 435 Light Years

Starwatch - December 2024 - Sun 1st Dec 2024

Published 1st Dec 2024

The stars that shine at night do so from immense distances.

Starwatch - November 2024 - Mon 4th Nov 2024

Published 4th Nov 2024

We recently saw the destructive power of hurricanes Milton and Helene, as they cut a path of destruction through various states in the US. They left in their wake flooded businesses, broken roads, power outages, and other problems. The repair bill will run into billions of dollars.

Large Magellanic Cloud - Fri 1st Nov 2024

Published 1st Nov 2024

Distance: 163,000 light years Right Ascension 05 : 23.6 Declination -69 : 45

Starwatch - October 2024 - Mon 30th Sep 2024

Published 30th Sep 2024

After a spectacular encounter with Pluto back in July 2015, the New Horizons spacecraft was redirected to visit a more distant object, known as 2014 MU69.

OCTOBER’S DEEP SKY HIGHLIGHT - Sun 29th Sep 2024

Published 29th Sep 2024

M31—The Andromeda Galaxy Distance: 2.5 million Light Years

Starwatch - September 2024 - Sat 31st Aug 2024

Published 31st Aug 2024

Spring is just around the corner, and with it, comes the promise of warmer evenings and clearer skies. And hopefully the opportunity to spend more time looking up!

NGC 253 – Galaxy in Sculptor - Fri 30th Aug 2024

Published 30th Aug 2024

NGC 253 is the brightest member of the Sculptor Group of galaxies.

Starwatch - August 2024 - Tue 30th Jul 2024

Published 30th Jul 2024

f you're brave enough to venture outside these cold winter nights, you'll be greeted by the heart of our Milky Way galaxy directly overhead. Find yourself a dark space in your backyard on a clear moonless night, and look straight up.

The Swan Nebula - Mon 29th Jul 2024

Published 29th Jul 2024

M17 – The Swan Nebula in Sagittarius

Starwatch July 2024 - Mon 8th Jul 2024

Published 8th Jul 2024

Look up overhead on any of these frosty winter’s nights, and as long as you have a dark area away from direct lighting, you’ll see the band of the Milky Way shining brightly.

Merging Galaxies - Sun 7th Jul 2024

Published 7th Jul 2024

NGC 4038-4039 Merging Galaxies - The Antennae. Distance: 45 million Light Years.

Starwatch June 2024 - Sun 2nd Jun 2024

Published 2nd Jun 2024

About half-way up the northern evening sky, a bright star shines.

The Trifid Nebula - Sat 1st Jun 2024

Published 1st Jun 2024

M20 – The Trifid Nebula in Sagittarius

Starwatch May 2024 - Thu 2nd May 2024

Published 2nd May 2024

A myriad of bright stars adorn the late autumn evening sky.

Galaxy NGC 5128 - Wed 1st May 2024

Published 1st May 2024

Galaxy NGC 5128—Centaurus A

Comet Pons-Brooks - Wed 10th Apr 2024

Published 10th Apr 2024

Looking west on the evening of April 27., 30 minutes after sunset. Locate the orange star Aldebaran, then scan to the left until you come to a fuzzy spot in the sky. Train your binoculars on it, the comet will be 239 million kilometres away. Graphic generated with Stellarium planetarium software.

M104 - The Sombrero Galaxy - Tue 9th Apr 2024

Published 9th Apr 2024

M104 - The Sombrero Galaxy. Distance: 31 Million Light Years

Starwatch - April 2024 - Mon 8th Apr 2024

Published 9th Apr 2024

Some of the brightest stars in the whole sky can be seen during these crisp autumn evenings.

Starwatch - March 2024 - Wed 6th Mar 2024

Published 6th Mar 2024

What a wonderful time of the year this is to be observing the night sky. The weather is warm, the nights clear, and the Milky Way shines directly overhead!

Object of the Month - Mon 4th Mar 2024

Published 4th Mar 2024

Eta Carinae Nebula (NGC 3372)

Distance: 7500 Light Years

Right Ascension: 10 : 43.8 | Declination: -59 : 52

We can think of our location in the universe along the lines of an address. The street would be planet Earth, the local government area would be the solar system, and the country would be the Milky Way Galaxy.

The state would be the Orion Arm – a ribbon of stars that wraps part of the way around the galaxy.

The Milky Way is a disk that is about a hundred thousand light-years wide. It has a long “bar” of stars in its middle. Spiral arms extend from the ends of the bar and wrap all the way around the galaxy. They make the Milky Way look like a pinwheel spinning through the void.

The arms don’t contain more stars than the darker regions between them. Instead, the arms are like waves on the ocean. As a wave washes through the galaxy, it squeezes clouds of gas and dust, giving birth to new stars. Many of those stars are big, hot, and bright. So, they make the spiral arms look bright and blue. But such stars die quickly, so the wave of brightening doesn’t last.

A few shorter arms fill in between the major ones. And the Orion Arm fits into that category. It’s about 3500 light-years wide and 20,000 light-years long. At our distance from the centre of the Milky Way, the arm wraps only about a quarter of the way around the galaxy.

The arm is named for Orion because of the arm’s location in the sky. The stars of Orion are among its most prominent members. But the arm also includes almost all the stars that are visible to the unaided eye.

If we could go back in time, more than four and a half billion years ago, we could watch our solar system being born: a newborn star surrounded by developing planets, one of which became our own Earth. We also would see a vast cloud of gas and dust that was spawning many other stars around the Sun.

Of course, we can’t actually go back in time. But we can see what the Sun’s birthplace might have looked like simply by observing one of the brightest and easily recognised constellations in the sky.

Orion, the hunter, is high in the eastern sky these January evenings. It features three bright stars in a row, which make up Orion’s Belt.

Above the belt is a row of objects that makes up Orion’s Sword. If you look carefully, you’ll see that one of the stars in the sword looks fuzzy. That’s because it’s not a star at all. Instead, it’s the Orion Nebula (labelled M42 on the star chart), a cloud of gas and dust that’s giving birth to thousands of stars. To the eye alone, it looks like a faint, murky smudge of light. Binoculars reveal the brightest of those young stars, while a telescope shows many more.

Four of those stars are called the Trapezium, because of the shape they form. Each of the stars is less than a million years old. That’s a lot of years by human standards, but the blink of an eye for stars.

The Trapezium’s stars are much hotter and brighter than the Sun. That’s because they’re also much more massive than the Sun. Such heavy stars burn through the nuclear fuel in their cores at a fantastic rate, which makes them shine brilliantly.

Like the nebula itself, the stars of the Trapezium are about 1500 light-years away. The brightest member of the quartet is just visible to the unaided eye, but you’ll need binoculars to see the others.

If not for the Trapezium, we wouldn’t see the Orion Nebula at all. The stars produce a lot of ultraviolet energy, which is absorbed by the nebula’s gas. This boosts the energy level of the atoms that make up the gas. When the atoms return to their normal energy level, they emit light, making the Orion Nebula shine brightly.

Astronomers recently discovered how this great star creator may have formed. They’ve found that the nebula is just a small part of a ring of dust that’s 330 light-years across. This suggests that a cluster of hot, bright stars once inhabited the ring’s centre. Their radiation pushed on the surrounding clouds of gas and dust, causing them to collapse and give birth to new stars. One of those clouds was the Orion Nebula, giving us a view of a stellar nursery like the one that cradled the young Sun.

Below the belt is Orion’s orange shoulder, the star Betelgeuse. And above the belt is the hunter’s blue-white heel, the star Rigel. Both of them are supergiants, stars that are much larger, brighter, and heavier than the Sun. And both are destined to end their lives with titanic explosions.

And you can see the remains of one of these explosions not far from Orion. Almost a thousand years ago, it announced its birth in dramatic fashion, as a brilliant new star in the constellation Taurus, the Bull. It was bright enough to see in daylight for several weeks.

The Crab Nebula is a cloud of glowing gas that spans about a dozen light-years. It’s called the crab because its tendrils of gas resemble a crab.

The nebula was born when a heavy star exploded as a supernova, blasting its outer layers into space. The gas raced outward at millions of kilometres per hour, so it’s spread out to form a big cloud.

At the centre of the nebula is the star’s crushed core, known as a neutron star. It’s roughly twice as massive as the Sun, but only about as wide as a small city. At such extreme density, a teaspoon of its matter would weigh as much as 10 million African elephants!!

The explosion that created the nebula also caused the neutron star to spin more than 30 times a second. And it created a magnetic field a trillion times stronger than Earth’s. As the star spins, the magnetic field causes it to beam energy into space. Radio telescopes detect this beam as “pulses” of energy, so the neutron star is also known as a pulsar.

Get your last look at “ring-less” Saturn before we lose it in the glare of the sunset sky. As our angle of view changes, we will begin to see the rings in their glory by end of 2026. As we draw the curtains on what has been the major feature of 2025, we re-open them to greet the colossus of the solar system, Jupiter. Look for it amongst the stars of Gemini in the north-east at the end of twilight. This behemoth will keep us entertained over the coming months as we watch the merry dance of the 4 Galilean moons around the planet. More on Jupiter next month.

The Moon is Full on January 3, at Last Quarter on the 10th, New on the 19th and at First Quarter on January 26.

Happy observing!